Destroy Language to Demonstrate Your Love for Writing and Speech

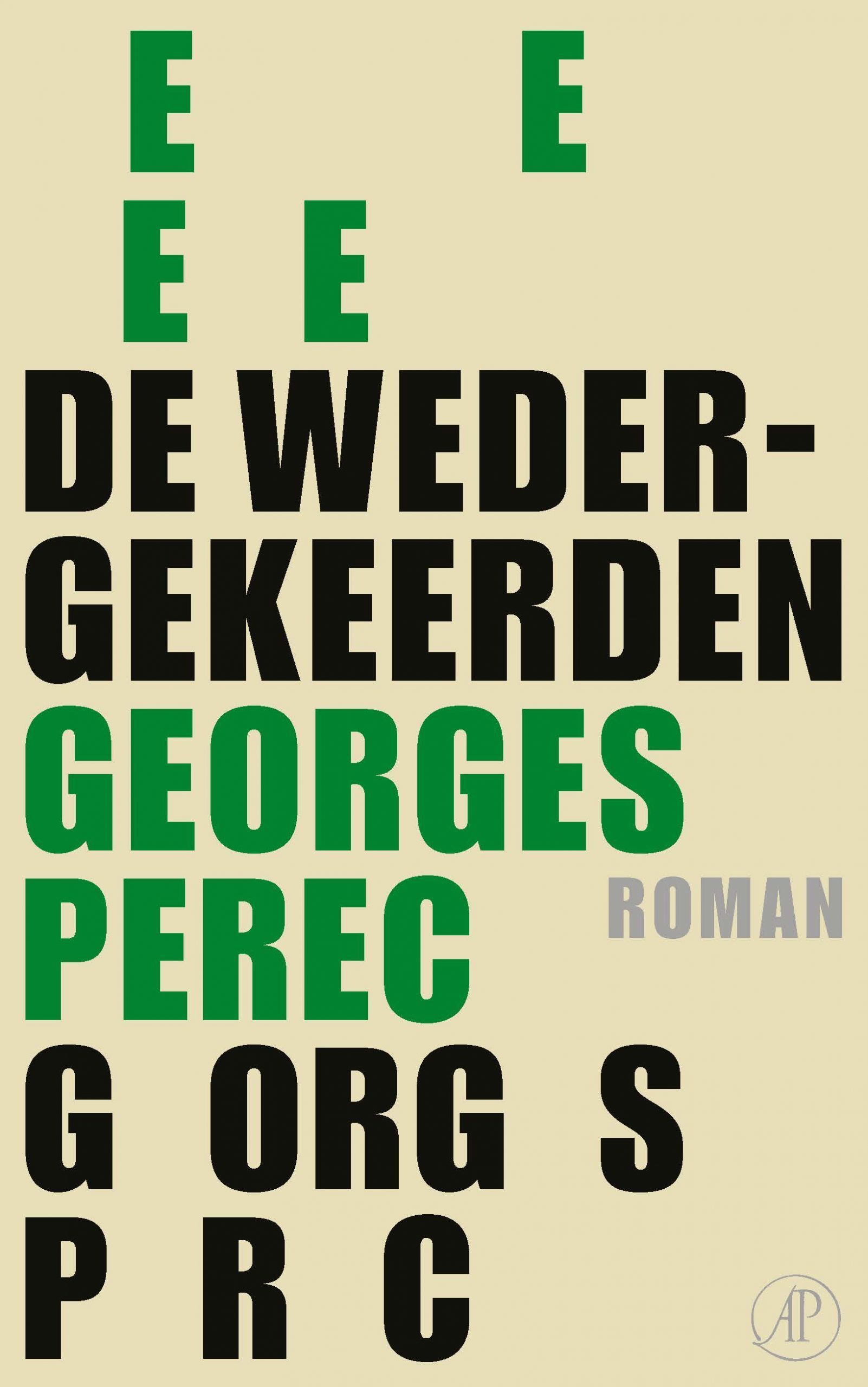

How do you show your love for language, according to linguist Marten van der Meulen? By playing, fooling around and experimenting with it, in the same way William Shakespeare, Georges Perec, and their translators Guido van der Wiel and Gilbert Adair did. With or without the letter e? That’s the question.

Early this year, an extraordinary book was published: De wedergekeerden, a Dutch translation by Guido van der Wiel of Les Revenentes by Georges Perec. A book that, despite its bizarre and scabrous story, is actually entirely about language. De wedergekeerden features only one vowel: the e. This sometimes results in magnificent sentences, such as the following profound reflection on the act of procreation on page 107:

Seks hebben betekent creëren per se, seks en creëren betekenen hetzelfde! Het ensceneren verpest de sfeer steeds weer en de begeerte ebt er verder mee weg. (Having sex means creating per se, sex and creating mean the same thing! Staging destroys the atmosphere every time and suppresses the desire further.)

Why on earth would you do that? Well, writing a book with only the letter e is an example of a constrainte, a limitation or a challenge. This was a characteristic of the literary movement Oulipo, to which Perec belonged. Followers of the movement tried to explore the limits of literature by imposing handicaps on themselves. A story where you don’t know the gender of the main characters, a dialogue that is entirely composed of punctuation, the same story told 99 times with a different writing style. You can think of anything and they have done it.

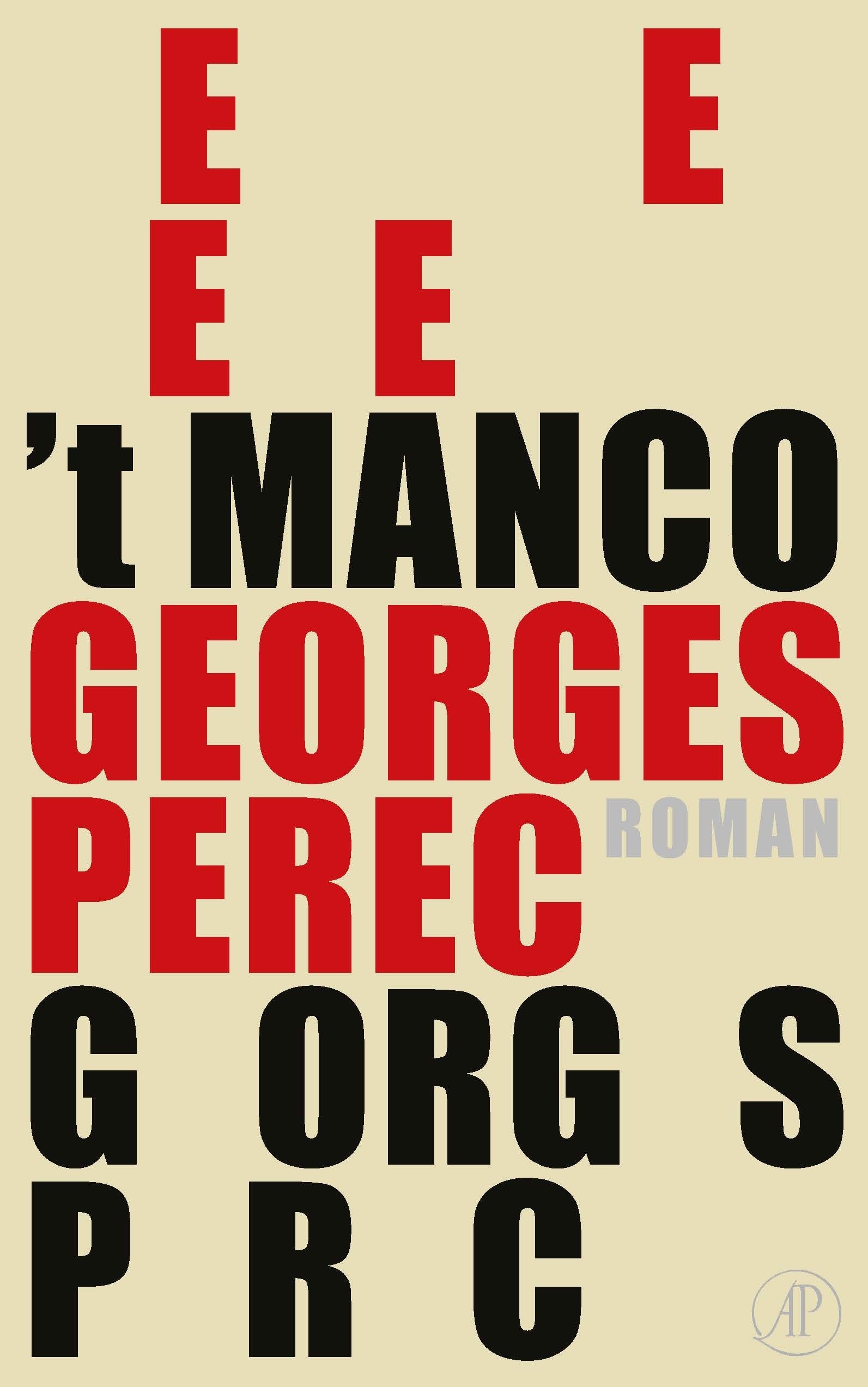

I have been a fan of Perec for some time already, since I read the counterpart to this new book a few years ago. In ‘t Manco (a Dutch translation of La Disparition, also translated by Van der Wiel) the letter e does not occur. Moreover, that missing vowel has a deep symbolic meaning here: it stands for the absence of the Jews after World War II (please read the epilogue for more information).

You might think: that with such a premise, it’s more about the form than the content, but nothing could be further from the truth. Indeed, story-wise ‘t Manco is brilliant, complex and even a bit exciting (I personally thought this was much less the case with De wedergekeerden). Yet the emphasis of this movement is mainly on the playfulness and especially the quality of those language games.

I realized this when I recently bought and read The Penguin Book of Oulipo. This English anthology contains work from (Oulipo) writers who both played and experimented with language in a similar way before the movement was born (this is called “anticipatory plagiarism”, how delightful!).

In the midst of this revelry, I returned to Perec. The anthology featured a translation of “The Raven” (by Gilbert Adair) without the letter e, the famous poem by Edgar Allan Poe. The poem is not published in Perec’s original French version, because every translator re-translates poems from the target language, English in this case. The title alone doesn’t work as it includes two e’s. This then becomes “Black Bird”. What follows is more or less exactly the line of the original poem, but without the letter e. The iconic phrase “quoth the Raven ‘Nevermore’ is changed to “quoth that Black Bird ‘Not Again’”. Only in the final sentences does the translator deviate from the original. There he reflects on what he is actually doing, still without using the letter e:

But it cannot stop from gazing for it truly finds amazing

That, by artful paraphrasing, I such rhyming can sustain

Notwithstanding my lost symbol I such rhyming can sustain

Though I shan’t try it again!

This is no fine piece of language game: it is elevated far above that. It’s an art that I can only have deep respect and admiration for. It’s madness already that Perec accomplished to do this. The fact that someone else was able to translate this, with the content more or less intact and the metre and the rhyme and the iconic one-liners, shows a notion of brilliance or almost insanity. In addition, there is the meta-commentary near the end, in which the translator unexpectedly reflects on his own work.

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare© Wikimedia Commons

It is reminiscent of Shakespearean lines in which he suddenly refers to the fact that it is theatre. Just think of the line “if we shadows have offended” at the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (the shadows are ghosts, but also stage actors, reflections of real people). Even more beautiful is the line “from forth the loins of these two foes” at the beginning of Romeo and Juliet. Loins would originally have been pronounced the same as lines in Shakespeare’s time. “From the lines of these two foes” thus. Magnificent, and Perec and his translators manage to do this without using the letter e!

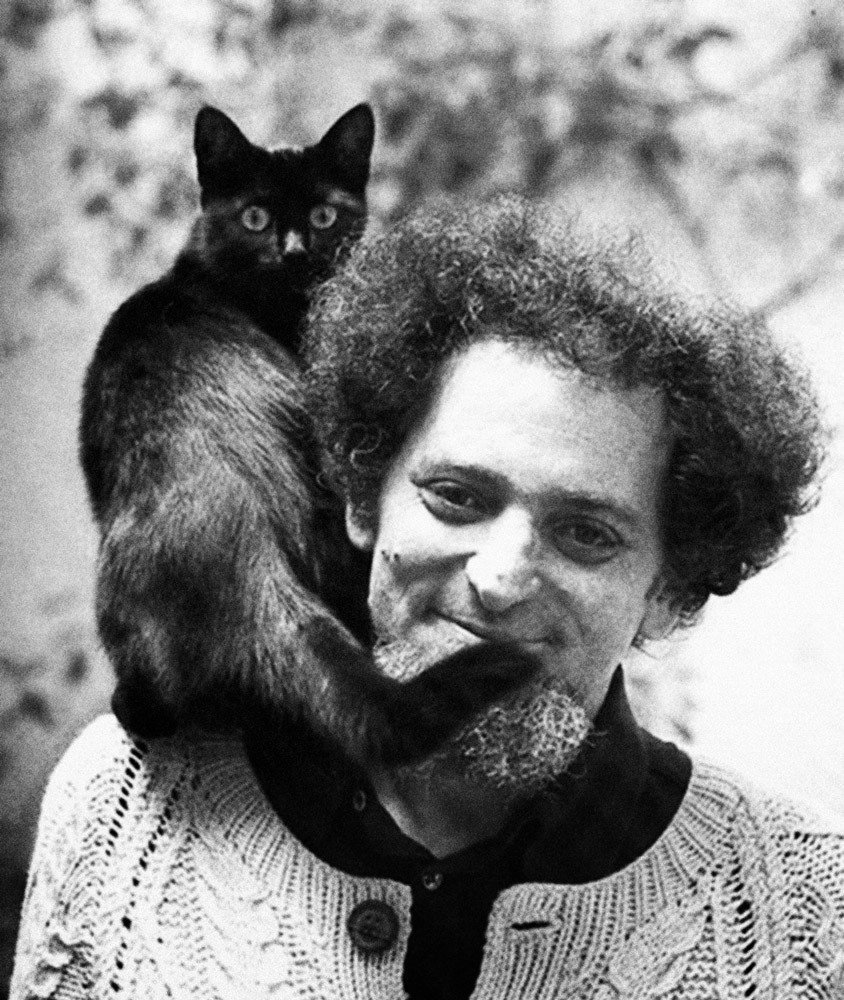

Georges Perec

Georges Perec© Wikimedia Commons

It may come across as elitist for me to bring up Shakespeare, but as an Anglicist, I have read all those plays, devoured them, and learned them by heart. Shakespeare is one of the greatest writers, and a language artist par excellence. Besides, these translations by Perec are pure, absolute, of incredible quality, that I have only ever experienced at Shakespeare performances at The Globe in London. I have been there three times, all of them are in my top five finest art experiences. Perec’s oeuvre, in particular ‘t Manco, is in there too.

For all people who don’t tolerate variation in language, no English, no slang, because they say they love language: this is what love for language looks like. Stretch it, force it into new forms, play, fool around, experiment with it. Let language live. If you do, you will go beyond your wildest language dreams. If I were a raven, I would say: forever more!